Do you want to know a secret?

What important truth do very few people agree with you on?

Peter Thiel, of PayPal fame, enjoyes asking interviewees this question and relishes hearing the answers.

Those answers he calls 'secrets'—ways of understanding the world most people are unaware of. Almost everyone knows a few secrets.

To become more successful, Thiel reckons we should actively seek out such secrets.

What secrets do you know? What have you discovered about how reality operates that would surprise many people?

My Secret

Today, I'll let you in on one of my programming secrets.

Because it's a secret, many software developers will disagree. Please maintain an open mind while reading this newsletter. :)

My secret works. It's hard to argue with the simple and focused code produced by this technique.

OK, so what is my secret?

Favour throwing exceptions over returning errors

If that statement is rubbing you the wrong way, I understand. I used to feel the same way. Just bear with me for 5 minutes.

Another way of expressing the same idea:

Throw an exception when the current operation can no longer continue.

For example, when user input validation fails, the conventional view is to return an error result.

The typical reason in favour of the conventional view, is that humans are fallible, and incorrect user input will happen and so represents an expected scenario.

Therefore, throwing an exception seems inappropriate. After all, exceptions are reserved for exceptional circumstances, like a database connection failing. Right?!

I disagree.

I will show you that you can—and should—throw an exception whenever you

- can no longer continue on the happy path, and

- want to inform the user of a problem.

Validation failures meet both these conditions.

For code simplicity, we should prefer throwing exceptions rather than returning errors, e.g. using the Result pattern.

And I will demonstrate as much today!

The Scenario

We're attempting to register a new customer into an ASP.NET Web API.

Since we prefer to structure our system along Clean Architecture lines, we are isolating the high-level domain business logic into a separate class, RegisterCustomerUseCase.

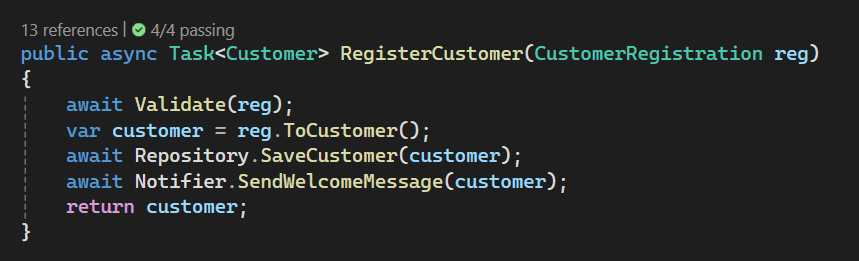

A public RegisterCustomer() method on this use case class provides executes the customer registration workflow. Data input validation is the first step in the workflow.

We have the option of handling validation failures in one of two ways:

- By returning errors, or

- By throwing exceptions.

First, let's consider returning errors.

A common approach here is the Result Pattern.

The Result Pattern

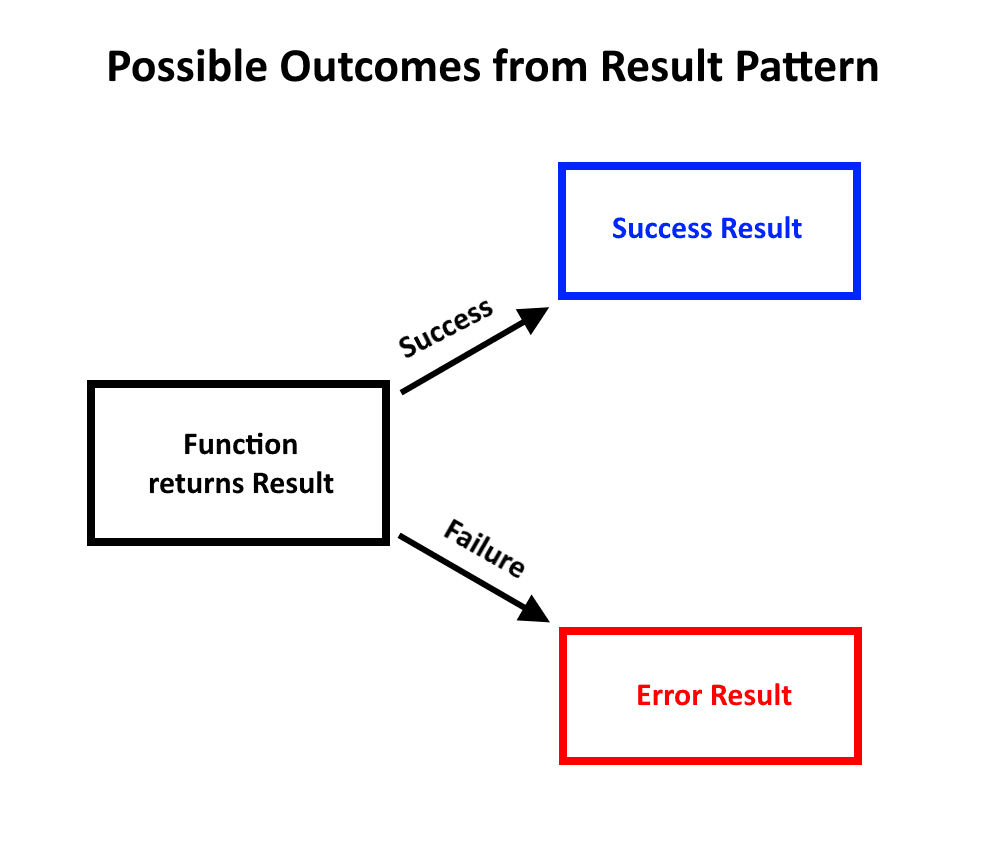

How does the Result Pattern work?

Here's how:

- If the operation succeeds, it returns a success value.

- Otherwise, it will return appropriate error information.

The Result Pattern gives our return values a split personality: One type for success and another for failure.

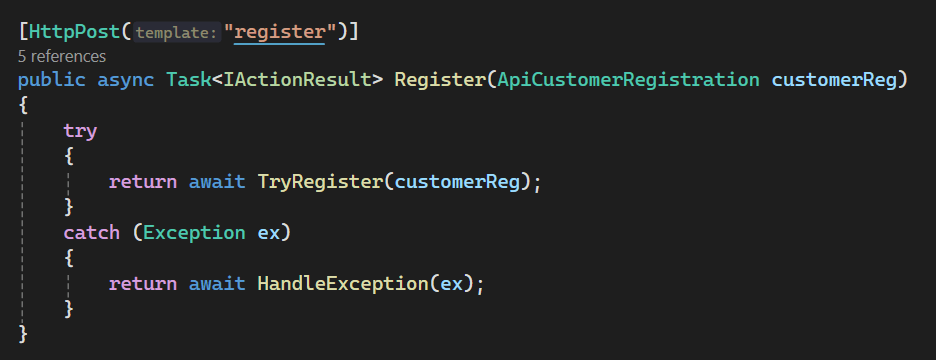

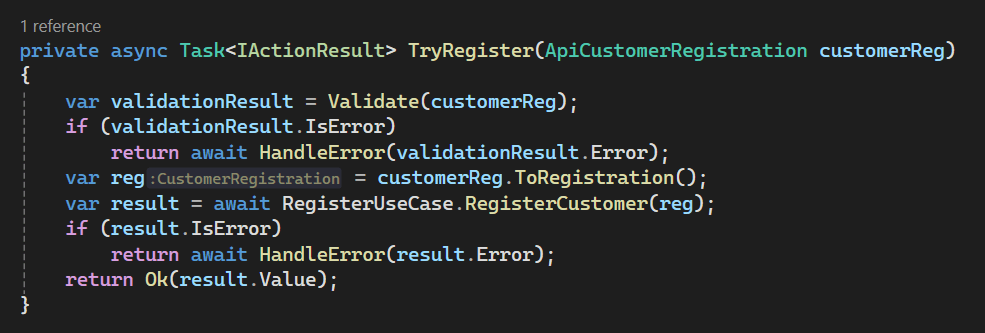

Let's check out the code when we employ the Result Pattern to register a new customer for the ASP.NET Web API controller action:

In the TryRegister() method, we can see two different error checks:

- First, after the call to Validate(), and

- after the call to the

RegisterUseCase.RegisterCustomer()

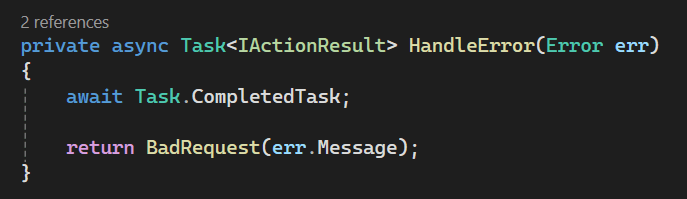

If it's an error, we call HandleError(), resulting in a 400 - Bad Request HTTP response:

Now we move to the business logic.

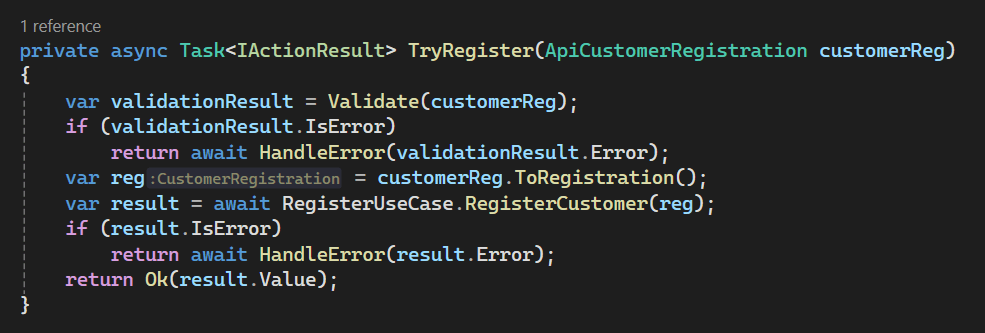

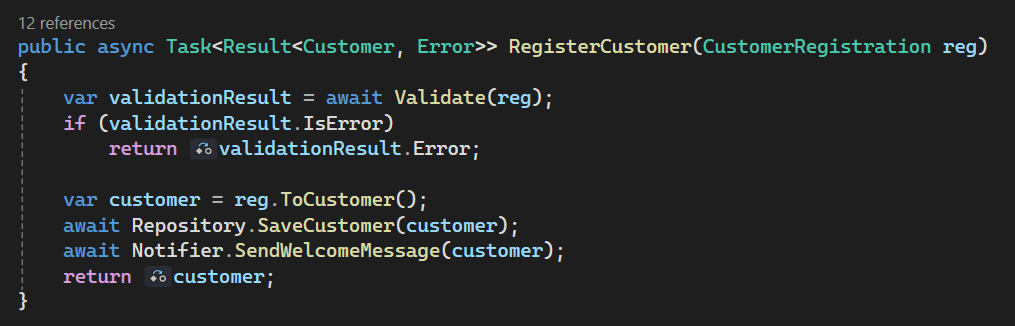

Let's examine how we use the Result Pattern in the RegisterCustomerUseCase's RegisterCustomer() method:

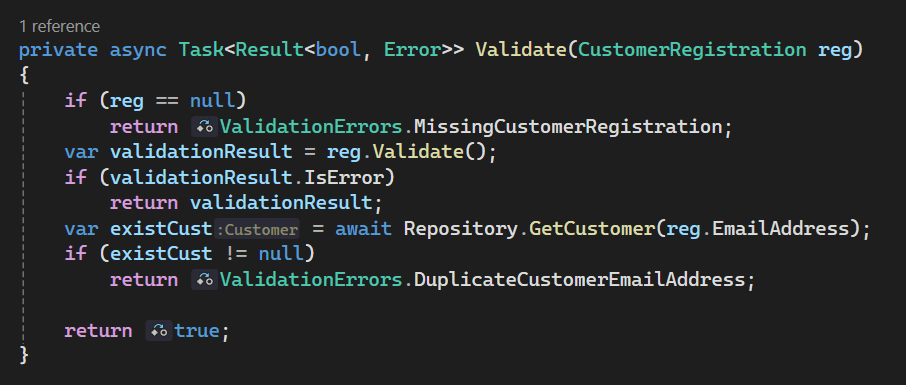

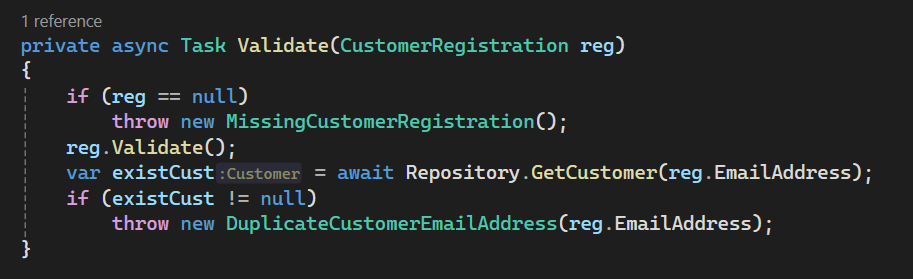

Notice how the first call inside RegisterCustomer() is to Validate(). What does this Validate() method do?

It's a little messy. In short, Validate() carries out detailed data validations, while RegisterCustomer() checks whether it got a validation error from Validate() and returns early if it finds an error.

No doubt, the Result Pattern works well enough.

However, every method returning a Result<Success, Failure> must be checked for the failure outcome.

When we do get a failure, it's usually fatal, and we want to get the error quickly back to the application boundary and user.

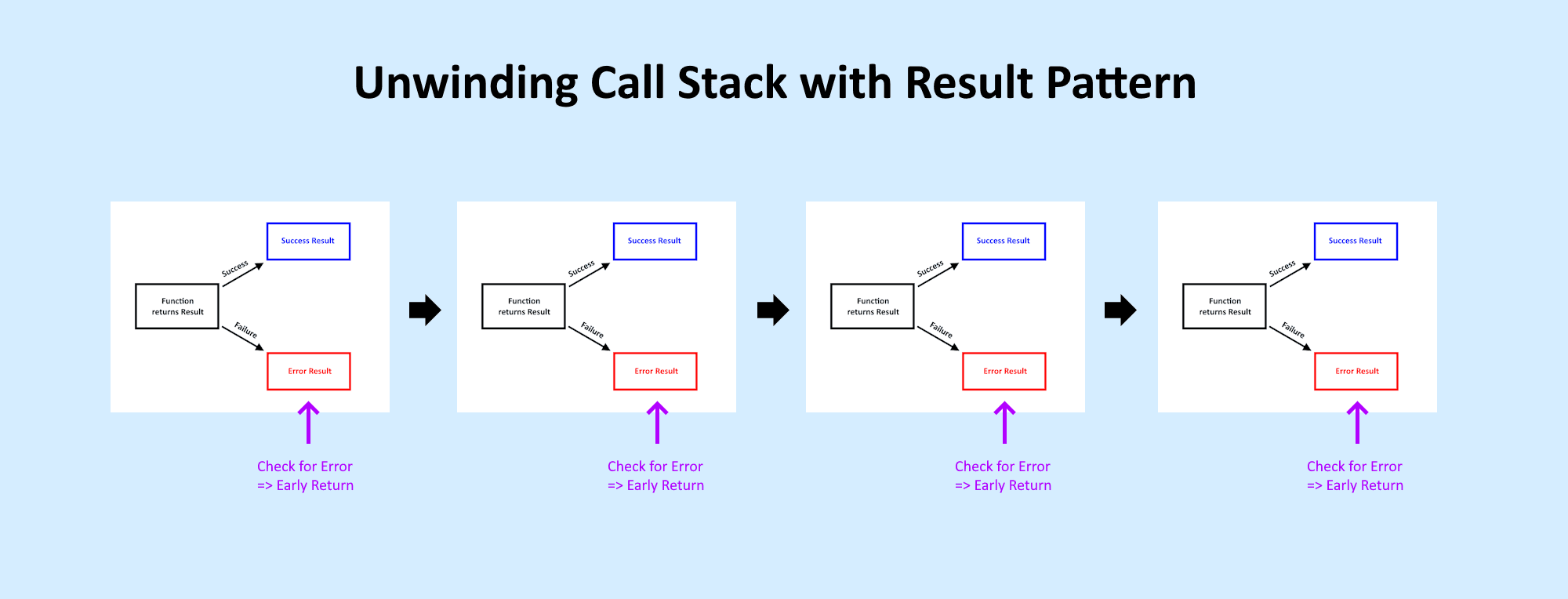

A depiction of returning errors up the calls stack:

Let's take a look at the alternative—Throwing Exceptions.

Throwing Exceptions

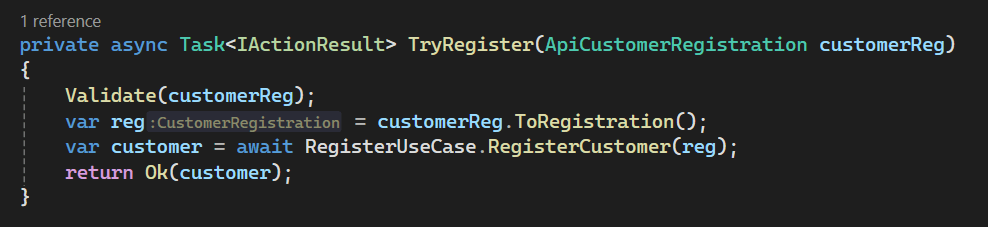

What would the controller action and use case code look like if we threw an exception when input data validation failed?

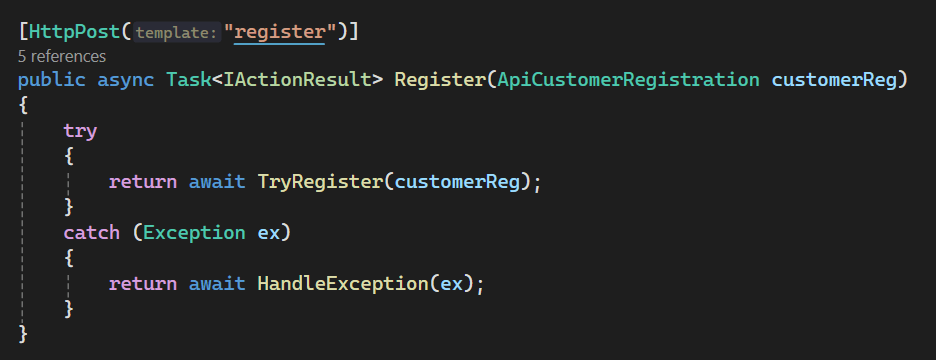

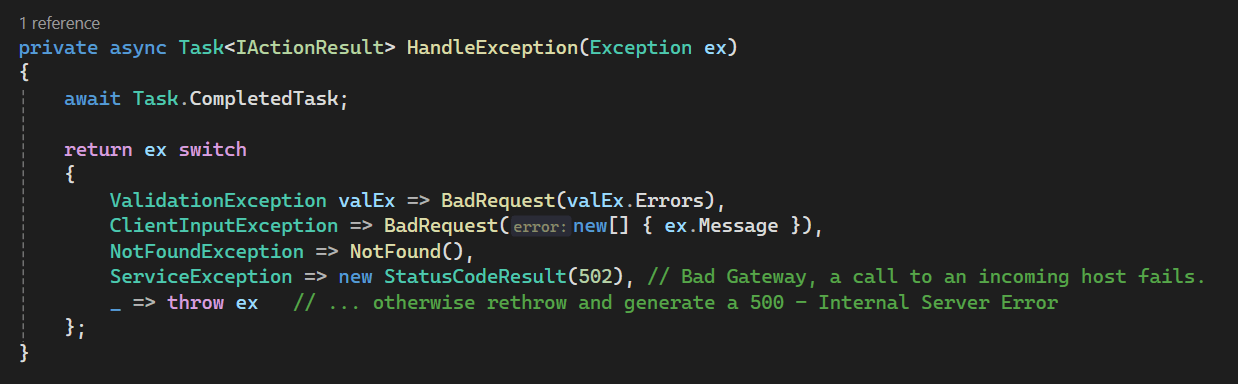

Let's find out. Here is the Controller code:

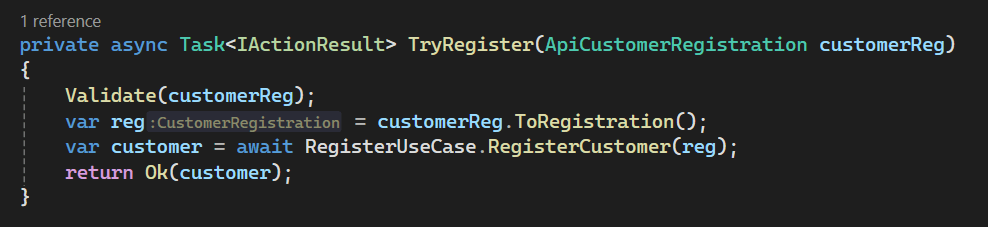

And here we have the RegisterCustomerUseCase methods:

Validate() checks for data problems and, if any, throws an appropriate custom exception.

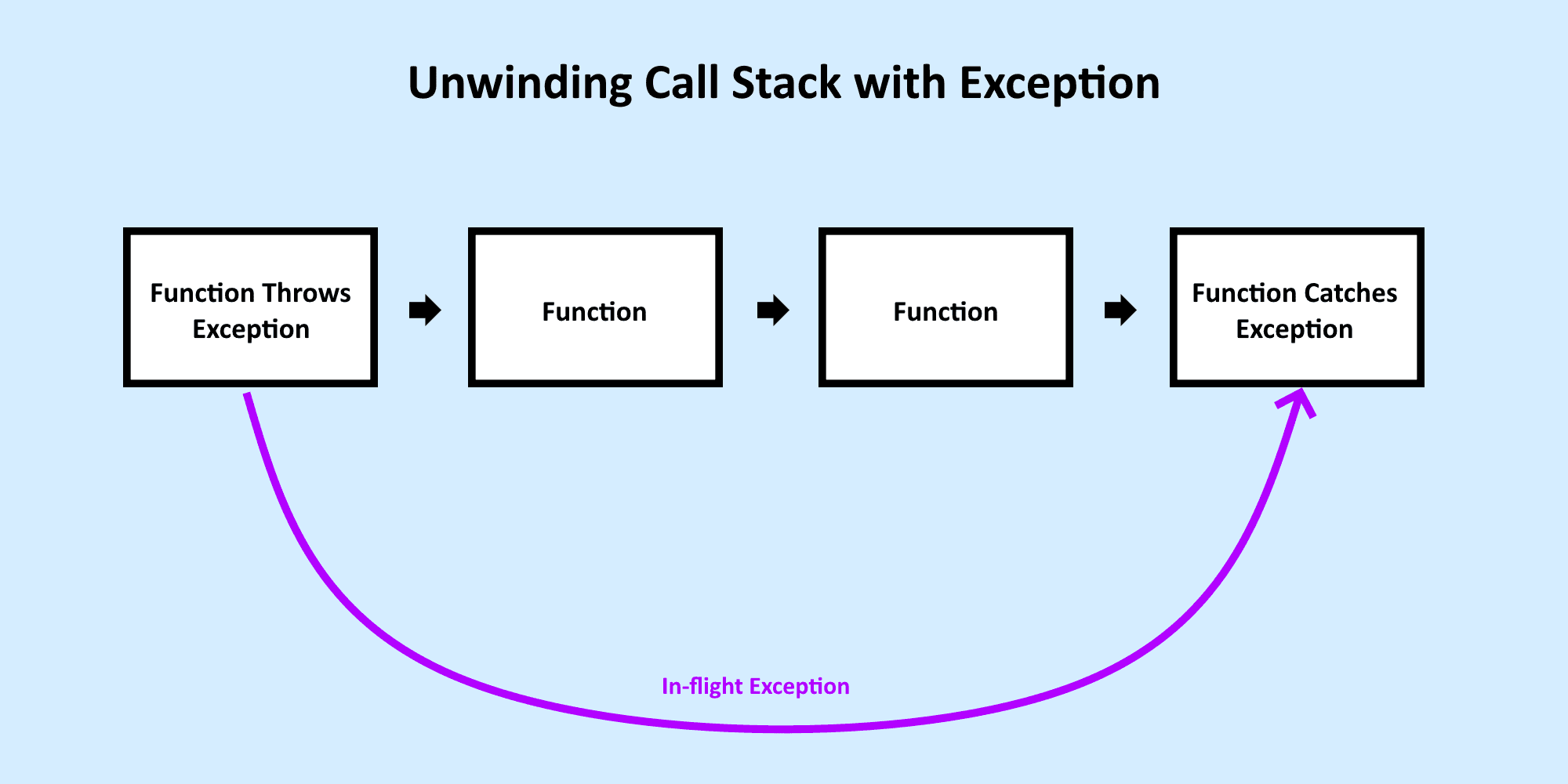

Once thrown, an exception will keep moving up the call stack until

- it is explicitly caught and handled, or

- it hits an unhandled exception handler

Functions that don't want to interact with an in-flight exception require no code to catch and manage the exception! This right here is the big, simplifying idea.

In other words, with exceptions, if we have 5 functions on the call stack, one will throw and exception, one will catch it, and the other 3 may be blissfully unaware of the exception!

What about the Result Pattern?

In the equivalent scenario, all 5 functions would need to be aware of potential errors; the 3 go-between functions would still require return value checks and early returns.

Here are a few other common objections (and their rebuttals!) to exceptions:

- "They are inefficient." - No, not really. Unwinding the stack when an exception is thrown is really fast and happens in microseconds. Whether you use the Result Pattern or throw exceptions, there will be zero noticeable effect on your system. Avoid premature optimisation.

- "When using exceptions like this, you're writing spaghetti code." - No, you're not. The GOTO statement allowed you to leap all over the code. Exceptions, on the other hand, only ever travel one way: Up the call stack. We can reliably catch exceptions at the application boundary.

- "Throwing an exception in one place and catching it in another, couples both places to the exception type and creates a fragile design." - The opposite is true. When we catch and handle base exceptions, we can create many specific custom exceptions and know we catch and manage these exceptions consistently.

Conclusion

OK, now you know one of my programming secrets. It took me a long time to work this out because of routine opposition. But in the end, this opposition made my strategy more robust and reliable, as it had to stand up to lots of criticism.

In the meantime, many aspiring software craftsmen who cared about their craft have switched over to preferring exceptions.

I love the clean, simple programming model provided by exceptions!

One more time, I give you the listings for TryRegister() side-by-side for comparison:

To sum up. Both approaches work. There is nothing wrong with the Result Pattern. You can return errors from functions and check return values for failure.

Or you can throw exceptions.

I'm here to explain and give you options.

In the end, it's your choice. :)

Thanks for reading! I hope you found this edition of The 1% Developer helpful. I'm always happy to hear your feedback. Enjoy the rest of your week! All the best, Olaf

To get access to the source code for these examples, please check out my Patreon community

Footnotes:

[1] Generally but now always true. Java has checked exceptions which must be caught or declared in the method signature.